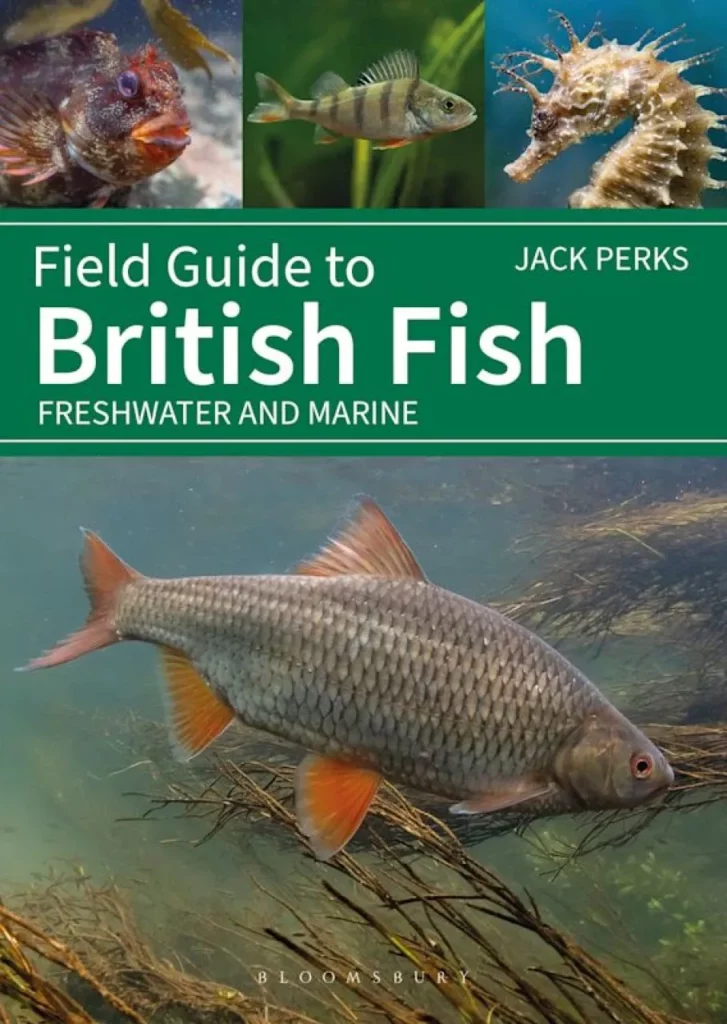

Field Guide to British Fish: Freshwater and Marine

Jack Perks

There is no shortage of field guides here in Britain, all of varying degrees of quality, and it seems most of their attention is focused on plants (~3,445 spp.), fungi (~15,000 spp.), birds (~640 spp.), and even insects (~24,000 spp.). Despite the sheer volume of these taxa, authors tend to focus on the same two or three hundred most frequently observed species; I suppose this makes a perfectly safe field guide, but for the bibliophile, it can get rather stale. For the lesser-known species which get virtually no coverage in anything other than their original description, the casual observer seldom knows the features to look out for, or even if they have spotted them without realising. This is where Jack Perks bucks the trend with his fantastic Field Guide to British Fish, having included well over half of all reported fish species occurring in Britain and Ireland – virtually every species you could encounter without venturing into seriously deep water (where the fishes start to become even more unusual), and far more than is feasible for a single person to photograph. In fact, the author photographed over half of the species which appear in the book, himself; all underwater – Britain’s answer to Ivan Mikolji, the popular underwater photographer from Venezuela.

Front Matter

At 272 pages with a coated paper that is not too thin, and a flexible, splash-proof cover, you would expect the book to be heavier than it is. Fittingly, this mirrors the content itself – compact and concise. The book immediately greets you with an intriguing question, ‘When does a fish stop being British when we’re talking about the sea?’, something that you will ponder as you work your way through the pages, meeting introduced species, migratory fishes, and visitors (a number of which are now year-round residents) from the Mediterranean.

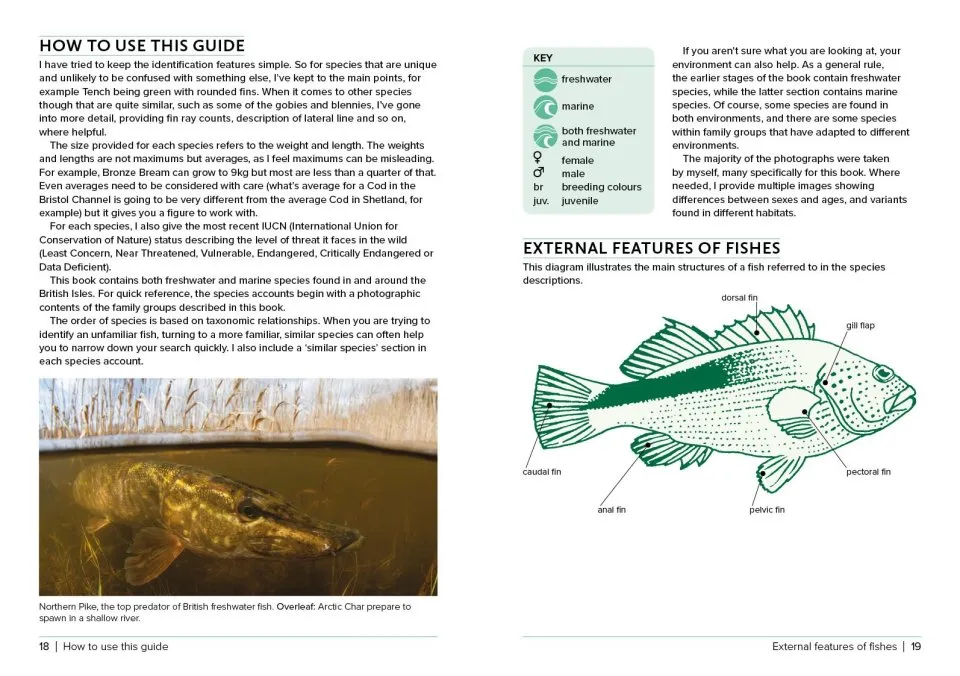

Over the next few pages, the author gives you some general background on fish breeding habits, senses, and the types of habitats you will encounter several species (even including exact locations to rock-pool, pond-dip, or dive), leading quite nicely to an overview of the so called ‘fish twitching’ hobby (from ‘twitching’, slang for an obsessive subset of birdwatcher). Right before we get into the meat and bones of the book, we come to a spread explaining how to read the icons and abbreviations used throughout. The author does not shy away from tackling sexual dimorphism, breeding colours and juvenile stages, where possible, which is something I am sure readers will appreciate; no one species looks the same throughout its entire life. It was particularly interesting to see the juvenile markings of British Barbel, which cause much debate on identification forums, with less-experienced observers believing they are instead Gudgeon.

Species Families / Species Accounts

Now we arrive at the species themselves, which are neatly arranged into 46 subsections, named ‘Species families’, serving as a secondary contents list, with each subsection having a picture of one of its member species to represent it and the page numbers it can be found on. While the first two subsection names are actual recognised families (cyprinids, salmonids), many others are positioned into higher or lower clades, using their colloquial name, others are an informal mix of different families, and some clades listed, such as mail-cheeked fishes, have several of their members included in different subsections. Warbonnets, eelpouts and gunnels have been placed in the blenny subsection (as they are blenny-like), whereas sculpins, wolffish, gurnards, and sticklebacks each have their own subsection, when all of them should be positioned within the mail-cheeked fishes1, if we were to be consistent. For the purposes of communication, however, I understand the reason for splitting them, and for the layperson I think this approach avoids more confusion than it creates. For example, if your general reader encounters a species of bullhead, they are more likely to search for them in the sculpin subsection than they are in the mail-cheeked fishes subsection, but I do wonder if there is a better and more consistent way of organising them.

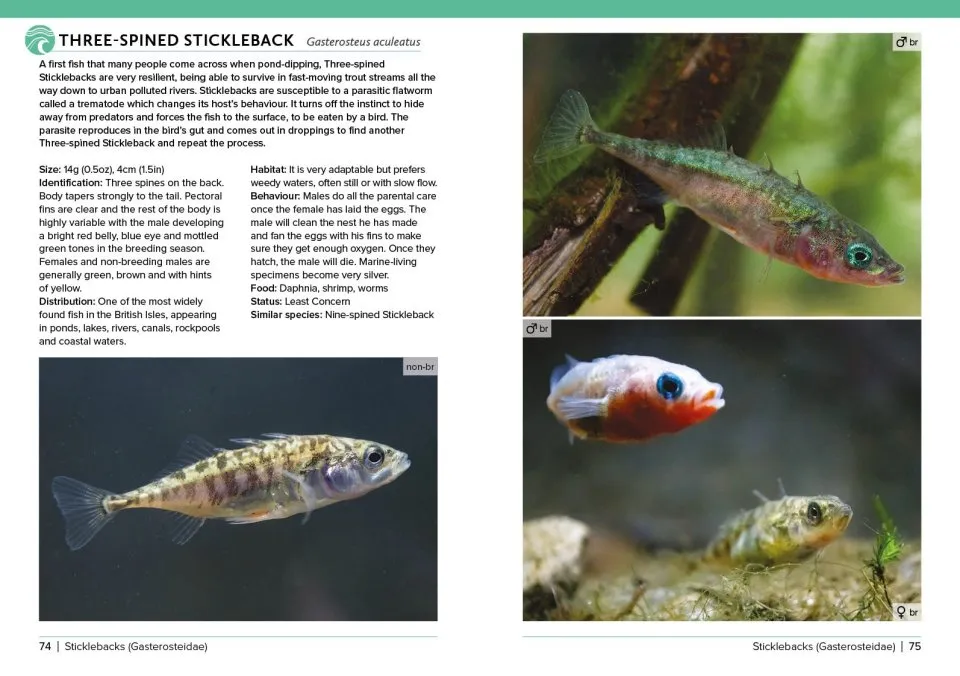

The next 220 pages impressively cover 200 species of fish, starting with freshwater at the front, and saltwater further in, along with euryhaline species sprinkled in among them (with an icon to identify each next to the species’ colloquial and scientific name), although a couple of the ‘family’ subsections contain both fresh and salt. Each species page details length, weight, and the discernible features you will need to know for identification, which is complemented perfectly by the author’s directions to similar species, allowing you to easily check out those pages for comparison – something which proved immensely useful to me, especially once I got to the flatfish section. There is a summary on distribution and the biomes inhabited by the species, along with their IUCN Red List status, which gives you some context as to whether the species you have encountered is typical or perhaps even scientifically significant in the location you found it. For dedicated fish twitchers, the information on diet and behaviour (especially if it differs throughout the year) might narrow down the search area for specific species, and may even help ‘crack the code’ for species hunters looking to catch them on rod and line. Praise should be given to the photography, as all images are of high quality: crisp; rich in colour but not saturated, and easy to use for identification purposes. Many fish are photographed in-situ in their respective environments, which is preferable to guides that use pictures of washed-out, dead specimens, or serviceable illustrations which can be a little ‘uncanny valley’. The very nature of fishes, being out-of-sight and out-of-mind, means that even the popular or most familiar species are left by the wayside when it comes to conservation funding and awareness, so it is refreshing to see the spotlight on those and the far lesser-known species that are given attention in this guide. Not only will this book show you staples from every other fish field guide, such as Atlantic Cod Gadhus morhua and European Bass Dicentrarchus labrax, but it will also share rarities such as Bluntnose Sixgill Shark Hexanchus griseus and Butterfly Blenny Blennius ocellaris. The author has put in the effort and mileage to photograph as many of these obscure species across the isles as possible. He even produced his own YouTube series, ‘Chasing Scales‘, which provides a ‘behind-the-scenes’ insight on this book, with Jack travelling to Ireland to LRF (light rock fish) for Red-Mouthed Goby Gobius cruentatus, Scotland to charter for Blackmouth Catshark Galeus melastomus, and even meeting with me in Cornwall to find Red Sea Bream Pagellus bogaraveo and the subtropical Ringneck Blenny Parablennius pilicornis. It was also pleasing to see our only native freshwater bullhead species recognised as Cottus perifretum instead of C. gobio, making it one of the first British books to acknowledge this, despite the change in nomenclature happening two decades ago (more on this in February 2025 issue of British Wildlife). You might notice some unusual additions in this guide too, such as the Burbot Lota lota, likely now extinct in Britain, but included due to the attention surrounding potential reintroduction programmes; or the Round Goby Neogobius melanostomus, a species not yet present in Britain, but extremely likely to become invasive here; it is included so that people may be able to recognise them quickly, should they make it here.

Like with any ambitious book, covering well over a hundred species, there will be some errors, even after thorough checking. The errors which I am able to notice are rather minor, and would not bother the vast majority of readers, though it might irk a few whose primary focus is on the genera in question. The book includes Shore Clingfish Lepadogaster lepadogaster, a species that the author says is relatively widespread here, and notes that the similar species, Cornish Sucker L. purpurea, is restricted mostly to Cornwall. However, the Shore Clingfish is not yet recorded in Britain (though it may be present on the south coast2), whereas the Cornish Sucker is found across much of Britain3 (its colloquial name refers to the region in which it is predominantly found, but British populations are not endemic to Cornwall). Another clingfish featured is the Two-spotted Clingfish Diplecogaster bimaculata, our deepest water clingfish found primarily from the lower shore down to depths of 55m4 (as opposed to the upper shore or intertidal zone, like our other clingfishes). The book says that the Two-spotted Clingfish can also be found in shallower water (not an error, but it is unusual for the species) and incorrectly uses a photograph of what appears to be the more common (and unfortunately absent from the book) Small-Headed Clingfish Apletodon dentatus in its highly variable reef markings5. These two species are tricky to tell apart when both adorn their overlapping reef markings, though Two-spotted Clingfish typically show a large spot on either side of their flanks. Next, an entirely different type of fish, but one with a similar name: the Two-spotted Goby. The author erroneously lists this as Gobiusculus flavescens, but this species was reclassified as Pomatoschistus flavescens in 20196; and the genus Pomatoschistus has been moved out of the family Gobiidae (typical gobies) to the Oxudercidae (estuarine gobies, mudskippers & allies). Easy things to miss, as changes in the nomenclature of our mini-species are hardly (if ever) widely publicised. The final error is in the first sentence of the species profile for Black-faced Blenny Tripterygion delaisi, which is described as ‘Not a true blenny’. This is a myth that has persisted almost exclusively in British angling circles. The Black-faced Blenny belongs to the tripterygiid (triplefin) blenny family, which is nestled within the suborder regarded as the ‘true’ blennies, Blennioidei1. Interestingly, triplefins were the first of the blennioids to branch, making their lineage the oldest and most basal of all the true blenny families. An oversight as small as the fish itself, but one to note for future editions. Overall, these are very trivial errors in what is an otherwise essential book to accompany you when ‘fish twitching’. The author has since revised these mistakes for the forthcoming e-book, and any future printed editions.

Appendices

The last few pages of the species section touch on hybrids, a bane for any keen observer, and rarely covered in any detail in other literature. The author explains the circumstances which lead to hybridisation, as well as meristic diagnostics to recognise some of the most common potential hybrids, all annotated by further high-quality photographs. The book rounds off nicely with the typical end matter you would come to expect in an appendix, but the pièce de résistance is the species checklist for readers to tick off the fishes they have encountered; a fun way to encourage readers to get out of the house.

Being a field guide, this book does not need to go into great detail with each species, most of them being allocated a single page and an abridged paragraph which explains a few defining or notable things about them, in addition to the previously mentioned facts. With the wealth of knowledge the author has, you know that more could be said about each species, with him easily achieving double or triple the pagination if the publisher would allow, although I would argue that would defeat the purpose of a field guide. It is difficult to imagine the amount of work that must have gone into this publication; understanding how hard it is to seek out just one of the rarer species in this book, I can testify to the achievement involved in photographing and documenting as many species as Jack has. I feel like the best compliment you can give a portative publication such as this one, is that it leaves you wanting to know more; encouraging you to pick up additional literature on the species of interest, perhaps something more cumbersome than you would normally carry in a rucksack or coat pocket on location. Field Guide to British Fish does just that, piquing your interest in an array of fishes, and stoking the flames of excitement around the ones you are most drawn to, before you inevitably fall down a rabbit hole of research and exploration. Not only has it thoroughly earned a place in my library, but it has also already found a permanent residence in my field pack!

View this book on the NHBS website

Reviewed by Josh Pickett

Josh Pickett is a conservationist and author, concentrating on overlooked or peculiar marine and freshwater fishes (www.joshpickett.co.uk).

- Near, T. J., & Thacker, C. E. 2024. Phylogenetic classification of living and fossil Ray-Finned fishes (Actinopterygii). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 65(1); https://doi.org/10.3374/014.065.0101.

- Henriques, M., et al. 2002. A revision of the status of Lepadogaster lepadogaster (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae): sympatric subspecies or a long misunderstood blend of species? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 76: 327–338.

- Wagner, M., et al. 2017. Lepadogaster purpurea (Actinopterygii: Gobiesociformes: Gobiesocidae) from the eastern Mediterranean Sea: Significantly extended distribution range. Acta Ichthyologica Et Piscatoria 47: 417–421.

- Ruiz, A., et al. 2007. Diplecogaster bimaculata bimaculata Two-spotted clingfish. Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews; https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/2177.

- Brandl, S. J., et al. 2011. First record of the clingfish Apletodon dentatus (Gobiesocidae) in the Adriatic Sea and a description of a simple method to collect clingfishes. Bulletin of Fish Biology 13: 65-69.

- Thacker, C. E., et al. 2019. Phylogeny, systematics and biogeography of the European sand gobies (Gobiiformes: Gobionellidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 185: 212–225.