Moss and Lichen

Elizabeth Lawson

Lawson’s Moss and Lichen is a hardback for every nature enthusiast’s bookshelf, where two of the greatest biological kingdoms collide in a beautifully illustrated and extensively researched piece of literature. This book is published as part of Reaktion’s Botanical series and is themed around the cultural and social history of lichens and bryophytes, discussing the biology and ecology of these taxa around the world. Moss and Lichen is a welcome addition to the collection of material already available, which shines the spotlight on these often overlooked and underappreciated lifeforms.

This book is divided into eight elegantly titled chapters, which guide you through the different elements of lichenology and bryology. The first two sections, called the ‘Cryptogamic Carpet’ and ‘Curious Vegetation’, provide insight into evolution and ancestry of mosses and lichens, their photosynthetic nature and ‘secret’ reproduction via spores. This sets the scene for delving deep into the biology and ecology of these taxa in the subsequent chapters, titled ‘Moss: Versatile Minimalist’ and ‘Lichen: Complex Individual’. There is an entire section dedicated to investigating the extreme conditions that these groups occupy, in ‘Cosmopolitan Extremophiles’, showcasing the versatility and resilience of these remarkable groups, as well as a chapter dedicated to bogs, named ‘Bogland’.

‘Literary Ecology’, one of my favourite chapters, compiles extraordinary examples of lichens and mosses represented in art and literature. This is followed by ‘Curious Observers’, covering great lichenologists and bryologists of the past and present. The book concludes with ‘#moss#lichen’, a fascinating chapter exploring the cultural significance of lichens and mosses across human history.

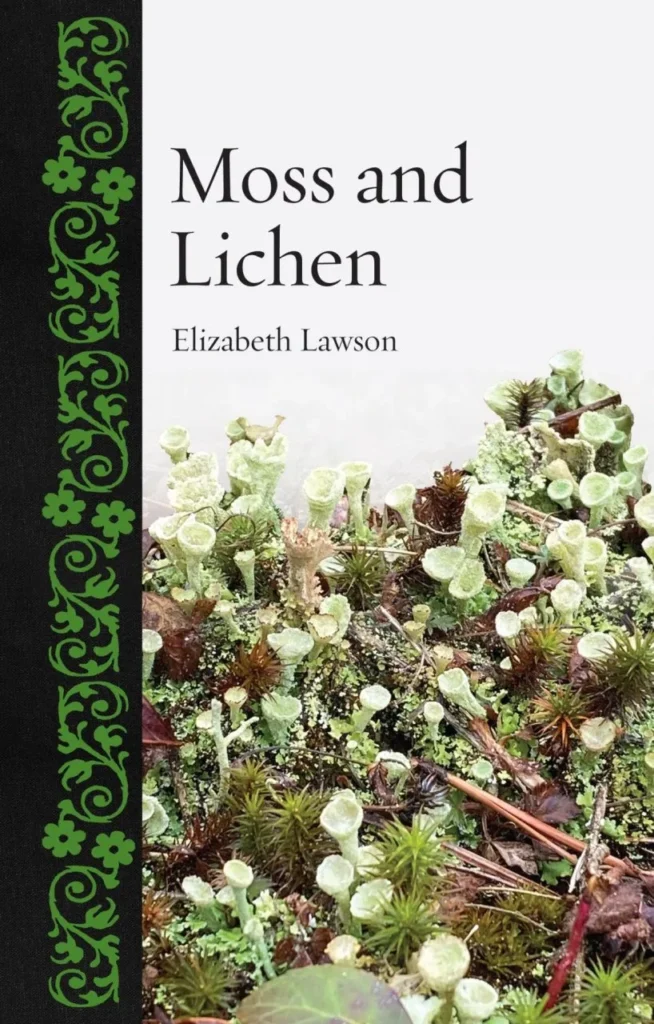

Lawson’s work is a source of inspiration and makes you want to travel the world and visit all of the wonders discussed and showcased in this book, from British Columbia to Namibia, and everywhere in between. It was great to see Britain and Ireland feature countless times in text, which is a reminder of the beauty that is exhibited in this part of the world and how incalculably lucky we are to have such a rich diversity of lichens, bryophytes and habitats to rival anywhere else on the planet. The photographs and illustrations within this book are beautifully curated, showcasing the intricate patterns, detailing, colours and textures found in the micro world around us. The inordinate amount of effort involved in sourcing and gaining permissions for the collection of images is clear, and certainly appreciated.

It was wonderful to recall many personal memories while reading the book – working with the British Lichen Society in the Scottish Highlands and the excitement when I first saw Solorina crocea, the Orange Chocolate Chip Lichen (p. 70). I was also delighted to see the gnarled and twisted oaks of Wistman’s Wood in my home county of Devon (p. 99), which is a site I have recently surveyed as well. In the Curious Observers chapter (p. 179) it was also great to have a page dedicated to the wonderful Becky Yahr, who played an important role during the early stages of my lichen journey.

Overall, I was amazed at the breadth of information, research and case studies that had been collated in this book – very impressive indeed! The encyclopaedic list of references can be found at the back, where this ‘one-stop’ publication signposts the reader to a wealth of sources consulted throughout the text.

Moss and Lichen is a technical read from the offset and is well-pitched at the intermediate to expert level. The sheer magnitude of information serves as a hub to direct readers to the plethora of scientific literature available on the subject matter. For those with a particular interest in the social and cultural history of mosses and lichens, this book should be a non-negotiable addition to your library, as there are few books I can think of in this field that are written so eloquently. It is unlikely I would recommend this book for general readers or to the average beginner who want to learn more on the topic, as there are more accessible books available. However, the illustrative material is stunning and the aesthetics of the book are definitely suited for all audiences.

It is important that the following critiques do not detract from what an impressive piece of work this is by Lawson. At times, though, it was difficult to fully connect with the book, as personal encounters and reflections from the author were limited. This is very much a literature-review style publication, offering a well-researched and well-cited overview of works that have been conducted by other lichen and bryophyte enthusiasts. This academic style will certainly suit some readers, but for those looking for a personal narrative and intimate account of these taxa, this book does not fill that niche. Including autobiographical detail would have done this book many favours, where personal anecdotes, feelings and thoughts from Lawson could have provided an opportunity to become better acquainted with the author and foster a sense of authenticity.

I do also feel that this book is overly ambitious and the quantity of information packed into 218 pages is excessive. Attempting to condense this extraordinary amount of information into a limited number of pages has repercussions. Although Lawson’s work covers an impressive breadth of information, at times there is an unfortunate lack of structure and coherence, leaving you feeling overwhelmed at the sheer quantity of content that is presented. The relentless streams of referenced work, case studies, research, facts and ideas jump from topic to topic, from country to country, from lichens to mosses and back again. This is particularly pertinent in the early chapters, where this scattershot approach makes this book a heavy read at times. The best chapters are those that are targeted on a specific subject.

Ultimately, each chapter in Moss and Lichen needs its own book to make the information less dense, giving the reader room to digest and reflect upon the content. This space could have been created if a more autobiographical stance was adopted. Although the ecology of lichens and bryophytes are entwined with one another, they are from separate biological kingdoms with vastly contrasting physiology and biology. Therefore, having two separate volumes, one for each group, would have been an easier feat and allowed the author to delve deeper and provide more time to reflect.

Moss and Lichen is a book that I thoroughly enjoyed reading and would be a welcome addition to any naturalist’s library. It has something to offer to all audiences, particularly those studying or working in the field. I have nothing but sheer admiration for Lawson’s craft and the phenomenal amount of care, time and patience required to produce this publication. Moss and Lichen provides a wonderful insight into the miniature world of lichens and bryophytes – I would encourage any naturalist to buy a copy of this book.

View this book on the NHBS website

Reviewed by April Windle

April Windle is a naturalist with a particular interest in lichens, especially those occupying our rainforest habitats along the western seaboard of the British Isles. She is currently self-employed and involved in a variety of lichen education and conservation projects, whilst co-chairing the Education & Promotions Committee of the British Lichen Society.