Lost and found: the mystery of Depastrum cyathiforme

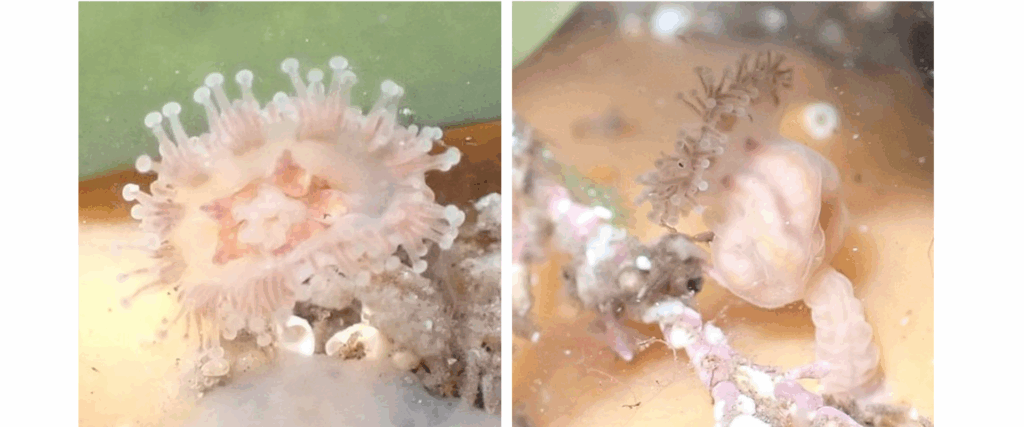

The first photographs of the stalked jellyfish Depastrum cyathiforme, taken at Pollachar, South Uist, in June 2023. © Neil Roberts

In June 2023, naturalist Neil Roberts came across four unusual animals in a rockpool at the southern tip of South Uist, in the Outer Hebrides. He took some photos and later, referring to online guides, identified them as Depastrum cyathiforme, a species of stalked jellyfish – relatives of the true jellyfish that spend their lives attached to seaweed or rock. Unknown to Neil at that time, these were the first photos ever captured of a species which, for almost half a century before, had seemingly vanished from the face of the earth. Here we share the story of the intriguing history and surprise reappearance of this enigmatic creature.

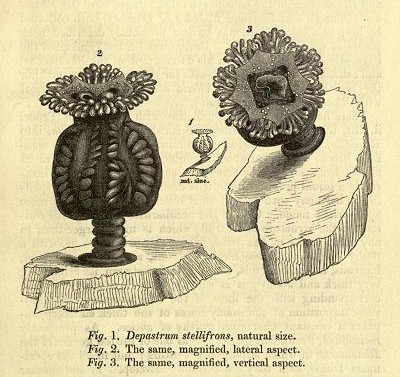

Almost everything we know about the stalked jellyfish Depastrum cyathiforme comes from naturalists of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. It appeared in the works of some of the famous marine biologists of the time, including the exquisitely detailed artworks of Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) and Philip Henry Gosse (1810–1888), who called it the ‘goblet lucernaria’. Their illustrations show a bizarre animal, with a wrinkled stalk leading up to a barrel-shaped body, the top of which was circled by a near-complete ring of short tentacles. Its appearance, particularly the lack of obvious ‘arms’, is a unique feature among the ten stalked jellyfish known to live in British and Irish waters (for an introduction to these fascinating animals, see our guide below).

Like a number of other stalked jellies D. cyathiforme was found in rockpools, but here its choice of habitat also set it apart from relatives; while other shallow-water species live on seaweeds and seagrass, D. cyathiforme attached itself to rock – so firmly that it was apparently impossible to remove it without damaging the animal.

It seems that this jellyfish was always uncommon. Gosse, for example, wrote in The Aquarium: Unveiling the Wonders of the Deep (1854) that D. cyathiforme is “apparently a rare species, since it seems to have been seen by only two observers, the Norwegian zoologist Sars, who first described it, and Dr. Landsborough, who gave it a place in the British Fauna, by finding it on the coast of Arran.“

Gosse’s illustration of D. cyathiforme from Weymouth, published in 1860 in The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany and Geology. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Contributed by Natural History Museum Library, London www.biodiversitylibrary.org

What are stalked jellyfish? Read our introductory guide below

Despite its scarcity, D. cyathiforme was nevertheless recorded from a range of locations in the century after Gosse published his account. David Fenwick’s website www.stauromedusae.co.uk – the essential source of information for all things stalked-jelly related – provides a comprehensive rundown of records of this species through history, showing a spread from Dorset to Orkney. Elsewhere, it was also known from mainland European coasts from northern France to Norway.

Then, sometime around the mid-20th century, the records dried up completely – not just in Britain, but worldwide. It was last seen in the UK on Lundy Island, in Devon, in 1954, while the last record anywhere was in France in 1976.

For an obscure species like this, the obvious question is whether it was truly ‘lost’, or just overlooked. D. cyathiforme certainly would be easy to miss; it’s barely 1cm in height, and could be written off as one of the miscellaneous – and hard to identify – small jellylike blobs you commonly find while rockpooling. However, there are good reasons to believe that there has been a genuine decline. Most compelling is the fact that its former haunts happen to be in some of the more active areas for marine recording in Britain, such as mainland south-west England, Lundy, Great Cumbrae and the Isle of Arran. Given that formal surveys and casual visits routinely locate many equally small and elusive species, it would be surprising if D. cyathiforme survived undetected at any of the more popular spots in these areas.

If the decline is real, identifying possible causes is essentially impossible given how little is known about this species. However, stalked jellyfish as a group are thought to be sensitive to water quality, which led to their inclusion as one of the protected features used in the selection process for Marine Conservation Zones. For D. cyathiforme, David Fenwick highlights the strong association with island sites which could – just possibly – suggest that this species was particularly sensitive in this respect. Coastal water quality has changed a lot since the time when Gosse and fellow naturalists were active, to the point that even sites well offshore, such as Lundy, are suffering the effects of nutrient pollution. Could it be that D. cyathiforme has been forced from all but the cleanest coastlines?

Whatever the reason, the lengthy disappearance and total lack of records of D. cyathiforme was cause for increasing concern; you cannot conserve something if you don’t know where it is, nor even whether it still exists.

Then, in June 2023, Neil Roberts made a surprise discovery:

“On holiday in South Uist in the summer of 2023, I took the opportunity of my friends being late-risers to pop down to the shore at Pollachar to do some rockpooling. At first the coast was a bit disappointing (miles of sand look wonderful, but don’t hold a great variety of wildlife), but then I found a pool with reasonable sized rocks. Turning over one of these rocks I found some interesting anemones and a small group of what I thought must be a species of Stauromedusan [stalked jellyfish], but not one I recognised. With some trepidation I put my newly purchased camera under the water and took a few photos.

When I got home, I started checking the Stauromedusae website. Their simple key pointed me to Depastrum cyathiforme, but the only representations given were pen drawings and watercolours. Still, the illustrations looked close enough to what I’d found for me to put a record into the Outer Hebrides Biological Recording Group with a suggestion that they might like to get it checked. Even so, there was still a niggle of doubt, and it was a relief recently when David Fenwick organised confirmation. Well chuffed, so I was!”

The shore at Pollachar, South Uist. Guy Freeman

Neil’s images depicted – for the first time – a creature which had previously been known only from paintings and line drawings, most more than a century old. The photos offer credit to the meticulous accuracy of Gosse and other artists, while also revealing new details of colour, shape and habits that weren’t captured in older illustrations.

The record came to the attention of stalked-jellyfish experts in 2025 when uploaded to the NBN Atlas and the identification was verified soon afterwards. After a long absence, D. cyathiforme had, finally, been located – not in one of its old haunts, but at a spot where it had never before been recorded.

Neil’s discovery raised two key questions. First, given that two years had passed since the find, was D. cyathiforme still there, or would this turn out to be a one-off appearance before the species again disappeared into the ether? I set out to answer this one in June 2025 and, after a few hours of searching the rocky outcrop on the picturesque Pollachar beach managed to find another single D. cyathiforme.

The single D. cyathiforme seen at Pollachar on a visit in June 2025. Guy Freeman

So, reassuringly, it seems likely that there is a persistent population at this spot, which brings us to the second question: does D. cyathiforme still survive anywhere else? The habitat at Pollachar doesn’t appear to be remarkable in any way – there must be countless similar shores on the Outer Hebrides and other Scottish isles, many of which may never have been explored to any great extent by marine recorders. Chances therefore seem excellent that further exploration could locate other populations in Scotland and, hopefully, elsewhere in Britain and mainland Europe, although we shouldn’t take this for granted; until more records emerge, South Uist is the only place globally where we know this species survives in modern times.

With a new visual image available thanks to Neil’s discovery, it is hoped that naturalists will keep this species in mind when exploring Scottish shores. Based on historical accounts, summer is the time to search and the favoured habitat is the underside of boulders or on rocks in shaded gullies in pools. Having now reacquainted ourselves with D. cyathiforme, we should take the opportunity to ensure that this jellyfish isn’t left to slip back into obscurity once more.

Stalked jellies: an introduction

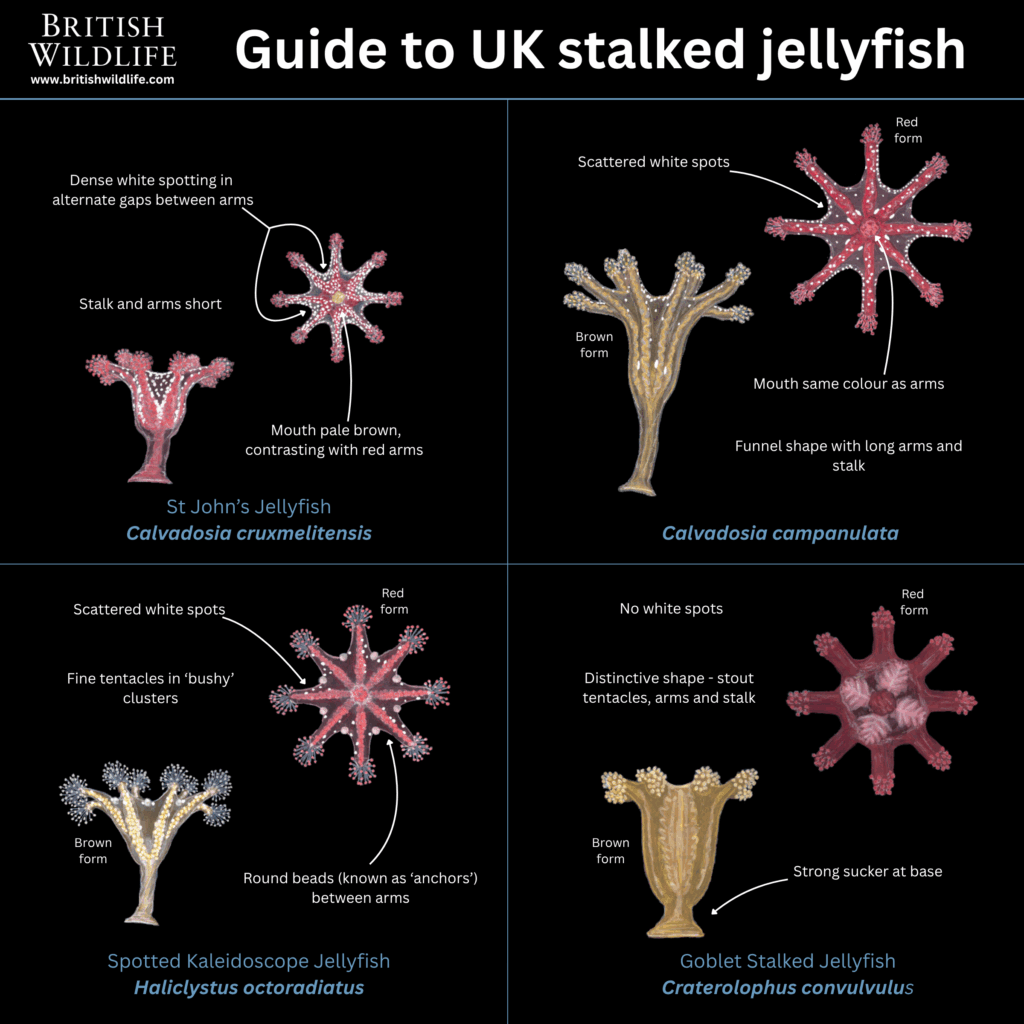

Stalked jellyfish are relatives of the true jellyfish, sea anemones and corals, all of which are grouped in the phylum Cnidaria. The shape varies between species, but typical features include a sucker used to attach to rock or seaweed, a flexible stalk leading to an umbrella-like body (the bell), and eight arms tipped with tentacles.

Most stalked jellyfish are small – under 5cm in height. They feed on small crustaceans and other animals, which are captured and subdued by stinging cells in the tentacles. They usually have an annual life cycle, growing and breeding through the spring and summer months before the mature individuals die off in autumn and winter.

Britain and Ireland are internationally important for stalked jellies, hosting ten out of the 50 species known globally. One of these, the St John’s Jellyfish Calvadosia cruxmelitensis, doesn’t occur anywhere else in the world, while a close relative, C. campanulata, is only found here and in north-west France.

A number of British species are found in shallow waters on brown and red seaweeds or seagrass, where various shades of olive-brown, red and green make them exceptionally well camouflaged. Although stalked jellyfish are present all around Britain and Ireland, diversity is much higher on western and northern coasts.

The simple guide below covers the identification of the four most common stalked jellyfish in British rockpools; for species accounts for all British and Irish species, visit the comprehensive Stauromedusae UK website.

From Guy Freeman, Editor of British Wildlife. For any potential new records of Depastrum cyathiforme, please send to Stauromedusae UK. Other records of stalked jellyfish can be submitted via normal routes to local/national recording schemes.