Twenty-five years on: a retrospective on the problems with rodenticides

In February 2000, British Wildlife published an article entitled ‘Problems with rodenticides: the threat to red kites and other wildlife’ written by Ian Carter and Alastair Burn. This article raised concerns about the burgeoning widespread usage of Second Generation Anti-coagulant Rodenticides (SGARs) and the associated impacts of secondary poisoning on predators and scavengers including Polecats, Barn Owls and particularly Red Kites.

The four main SGAR chemicals, difenacoum, bromadiolone, brodifacoum and flocoumafen remain in predominant usage in 2025 and their secondary impacts on wildlife have become apparent. Here we look back at the regulatory developments and real environmental impacts of rodenticide usage since the publication of this article.

History

By the 1960s and 1970s, Brown Rats had developed genetic resistance to warfarin and other ‘first-generation’ rodenticides. Consequentially, more effective and persistent ‘second-generation’ rodenticides became widespread with the four main SGAR chemicals coming into usage between 1975 and 1986. Each of the main SGAR chemicals has a significantly higher toxicity and persistence than traditional first-generation chemicals. This means that when species such as Barn Owls, Polecats, Buzzards and Red Kites prey or scavenge upon Brown Rats and other rodents that have ingested SGARs, they are at an increased risk of secondary poisoning.

The situation in 2000

The increase in fatalities associated with SGARs was first observed by the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) in the early eighties with the proportion of carcasses containing rodenticides rising into the early nineties before perceptibly levelling out. In the British Wildlife article from 2000, the authors used evidence gathered from MAFF Wildlife Incident Investigation Scheme (WIIS) and the Red Kite Reintroduction Programme to argue that usage of SGARs posed a greater threat to Red Kites and other predators/scavengers than was previously thought.

The evidence from WIIS showed a significant increase in residues of rodenticide found in deceased individual Buzzards, Barn Owls and Polecats. The authors note that the impact of SGARs is likely more significant than these results indicate as individuals killed by rodenticide are less likely to be discovered and analysed than individuals killed by other means.

The article serves as an interesting snapshot. Eleven years into Red Kite Reintroduction Programme, the small number of viable breeding pairs of Red Kites in Northern Scotland and Southern England were newly and successfully established yet extremely vulnerable to threats such as those posed by SGARs. As Red Kites are primarily scavengers and rely on Brown Rats taken as carrion for a large proportion of their diet, they are at an even greater risk of rodenticide contamination than other birds of prey. The article drew attention to the ‘worryingly high’ instances of rodenticide found in dead individuals and emphasised the difficulty of establishing SGAR contamination as a cause of death.

The authors’ conclusion expressed concern regarding an observed slowing of the population increase of Red Kites, a trend which correlated with the impact of SGARs. They emphasised the continued vulnerability of the species and called for the strengthening of efforts such as MAFF’s Advisory Committee on Pesticides which attempted to reduce the impacts of rodenticides on Red Kites and other wildlife. They also voiced support for increased practical action. At the time, English Nature and the RSPB had produced factsheets to spread guidance relating to the usage of SGARs.

What’s happened since

The 25 years since the publication of this article have seen a continuation of the controversies surrounding the now widespread usage of SGARs. The impact of rodenticides on Red Kites is now undeniable with WIIS data indicating that most individuals analysed since 2005 contained at least traces of SGARs.

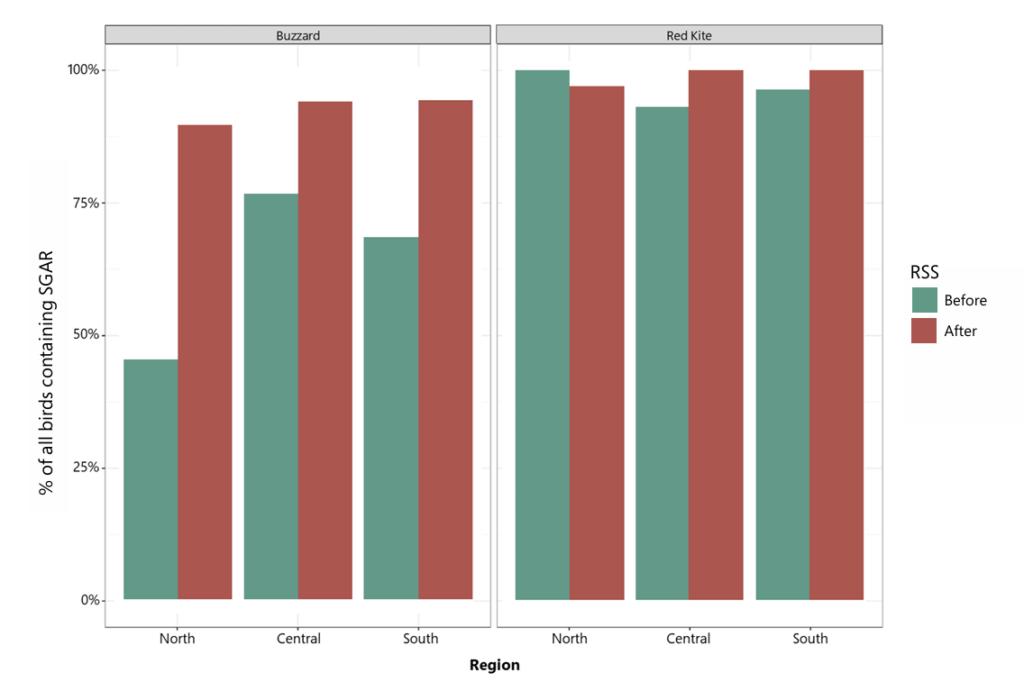

Governmental response to the problem has been slow, the most notable development being the establishment of the Rodenticide Stewardship Scheme (RSS) in 2015. The RSS was established to encourage ‘best practice’ with regards to continued usage of SGARs with the aim of minimising impacts on wildlife. The RSS has failed to improve the situation. The usage of SGARs has become more widespread and the consequences for wildlife have become increasingly detrimental. A recent report from Wildlife Justice (November 2024) based on data from WIIS between 2005 and 2022 has found that anti-coagulant rodenticides are now found in most Buzzards and Red Kites often at high levels in England.

The below figure, originally published in Wild Justice’s 2024 report shows the percentage of all birds showing SGAR contamination (at any level) by region of England. Periods up to and including the introduction of the RSS in 2015 are shown in green, those after in red.

Of the four main SGAR chemicals, brodifacoum is the poison most frequently found in Buzzards and Red Kites. Widespread contamination suggests that exposure results from widespread routine use. This means that the chemical is often used illegally through failure to follow statutory guidance and through the apparent deliberate targeting of scavengers and predators.

The recovery of Red Kites has been an undeniable success which has perhaps led to complacency on the real impact of SGARs. Despite the establishment of the species, it remains absent as a breeding bird across large areas of the United Kingdom. According to a six-year study conducted by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, SGARs were a contributory cause of death in 17% of the Red Kite cases. Without substantive and enforced regulatory changes on the usage of SGARs, the widespread prosperity of the species across Britain is unlikely to be actualised.

Similarly, despite a long term upward trend of UK Buzzard population abundance, progress has dipped since 2020. The decrease in population size has coincided with an increase in exposure to brodifacoum as outlined in Wild Poisoning Research UK’s 2024 report. A total of 43.1 % of Buzzards tested in the WIIS scheme in Wales and England between 2020 and 2023 were found to have lethal levels of Brodifacoum in the liver. While there could be other causational factors behind this drop in population abundance, the possible link to brodifacoum exposure levels should not be ignored.

Although the use of bromadiolone and difenacoum has been restricted to ‘in and around buildings’ in January 2025, there are no restrictions currently planned for the use of brodifacoum. Wild Justice’s report led to a series of parliamentary questions on the subject culminating in Defra’s response- a review will take place at an unspecified 2025 date. Whether this review leads to an end of the ‘light touch’ approach to regulation instigated by the RSS and we see an actual regulatory ban of SGARs remains to be seen.

This summary has focused on the detriment that the continued usage of SGARs holds for Red Kites and Buzzards in the UK. Unfortunately, the impacts of SGARs are geographically widespread and hold implications for a greater abundance of species. Research published in Springer Nature Link 2024 found that lethal levels of brodifacoum, difenacoum, and bromadiolone reside in the livers of almost half of 96 Cormorants and 29 Goosanders analysed around different German waters. Understanding of the extent of damage caused by SGARs across the global aquatic food web is only just beginning.

Carter and Burn’s ended their 2000 article with the statement ‘(t)he high public profile of the Red kite …(is) helping to raise awareness of this issue and, in turn, highlight the possible risks to a range of British wildlife’. This sentiment is echoed in Wild Justice’s recent report. The proven impacts of SGARs on Buzzards and Red Kites ‘serve as indicators of a wider problem that will affect other predators and scavengers, including scarce and declining species’. Twenty-five years have passed since the publication of ‘Problems with rodenticides’ and campaigners are still pushing for change and wildlife continues to suffer.

Problems with rodenticides: the threat to red kites and other wildlife and Ian Johnson’s prior consideration of Pesticide Poisoning of Wildlife in Britain are available in the back issues of our digital subscription or available for individual digital purchase.

By Sam Hackney