This book is a thorough reworking of the original Naturalists’ Handbooks volume 24, produced in 2013 by Gary Skinner and Geoffrey Allen. The greatly increased page count in this edition reflects the fact that both interest in our ant fauna and the amount of information we know about ants are far greater today than they were when the original was published. There is also much that we do not know about these industrious insects, however, and one of the later chapters encourages the reader to get out there and conduct their own studies. ‘Studying ants’ (chapter seven) includes descriptions of the many ways in which ants can be found, collected, preserved for later identification, and even cultured in ‘ant farms’ indoors, as many of us may have attempted as children. The attention to detail here includes a recipe for ant food to sustain your colony, including those all-important daily vitamins!

The introductory chapter sets the scene, with a brief overview of world families and how the UK fauna fits into this, for context. This ranges from the sub-family Myrmicinae, with over 7,800 species worldwide (but just 27 in Britain), down to the Martialinae from Brazil, which is known from just three specimens of a single species. This review introduces the fact that our fauna has been enriched over the years by the arrival of several so called ‘tramp’ species that have been hitching a lift around the world via commercial trade. Some of these (e.g. in the genus Hypoponera) are extremely difficult to identify and remain beyond the scope of this book, although the identification key provided appears to be very good (more of which later).

View this book on the NHBS website

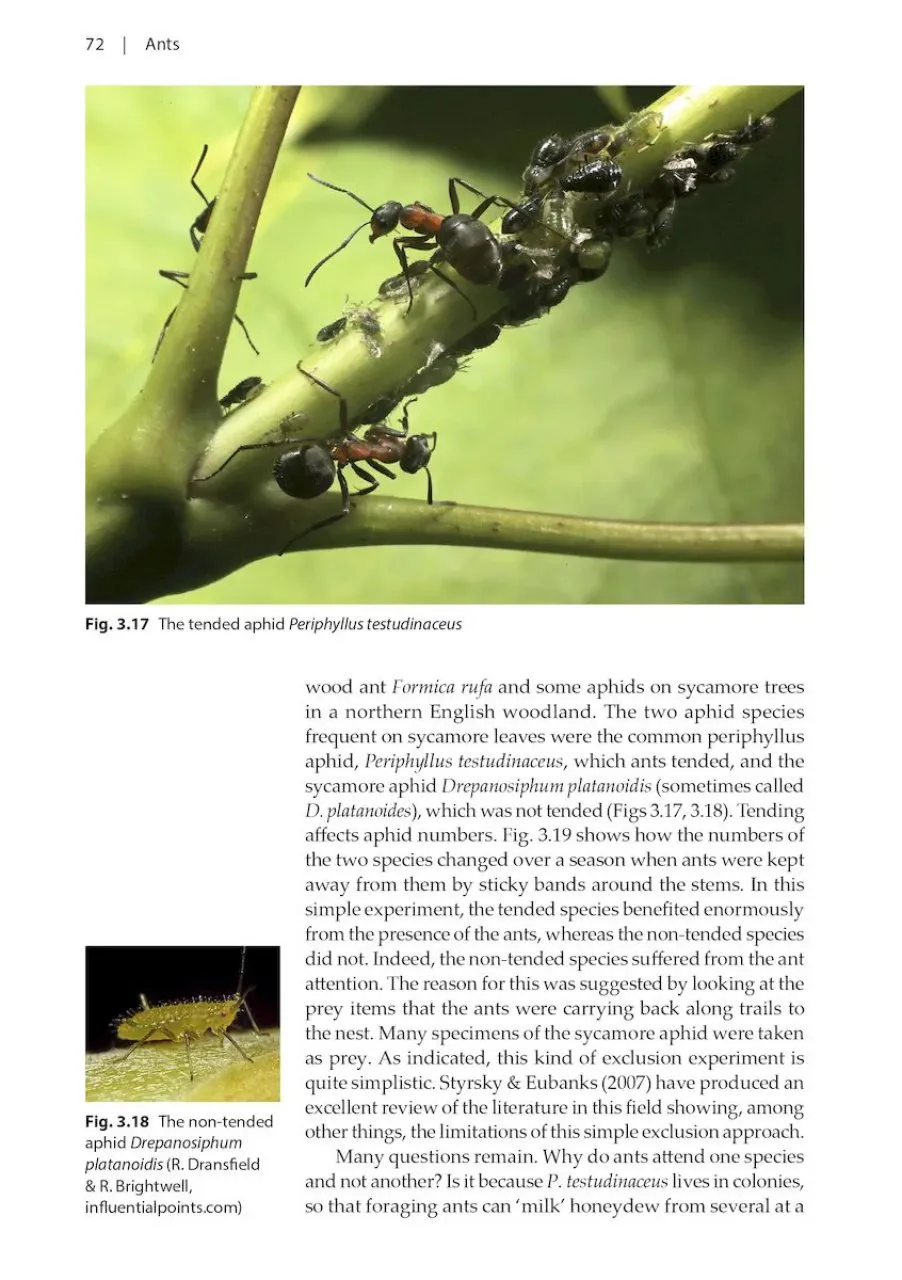

Chapter two explores the general biology of ants. Even the most casual natural historian will know that ants can live in very large social groups, akin to the lifestyles of Honeybees and bumblebees, with the large nest mounds of the various wood ants being the most impressive nesting structures. Not all ant species go for such grandeur, however, with the rare Temnothorax albipennis making its home and a much smaller nest within hollow plant stems. Ant lifestyles can be complex, with several species exhibiting temporary social parasitism when they take over the nest structures of other ant species. All these life-history facets are explained in an easily digestible manner.

For those primarily with a thirst for knowledge about the British species, this is first introduced in the chapter on distribution and abundance. This begins by explaining the general pattern seen in many insect groups in Britain, whereby species richness declines from south to north. This picture is made more complex, however, by the fact that one encounters ants that occur only in northern England or Scotland, so it is not as simple as merely ‘losing’ species as one travels from Dorset to the Scottish Highlands. There then follows a distribution map for each British species, using the same data-age class colours that are used by the Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society website. A brief summary here explains a little about each species, although more detailed ecological notes for some of the rarer ants appear in a later chapter.

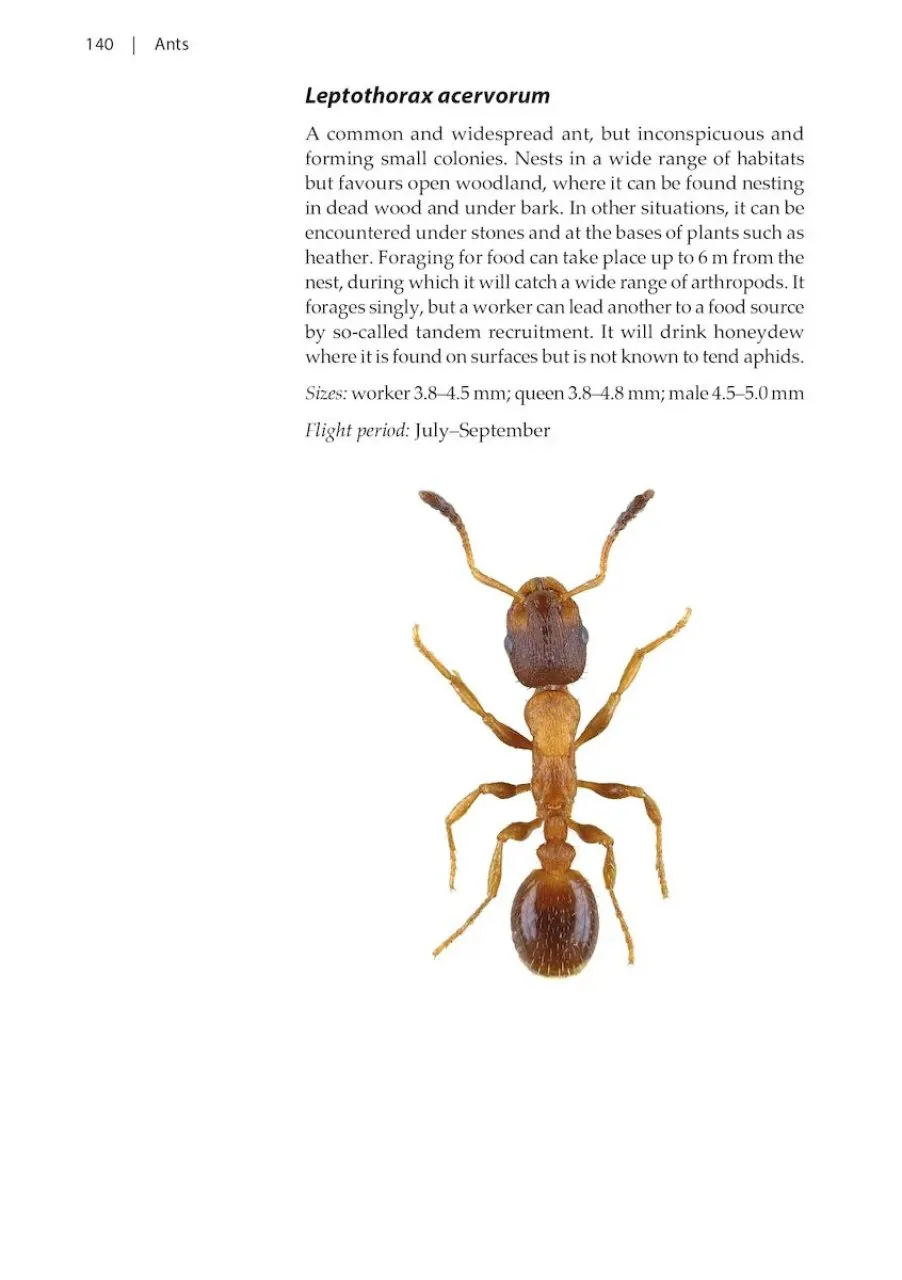

The chapter on identification is thorough and detailed, yet quite easy to comprehend. It does not beat about the bush in terms of requirements – you will need a stereomicroscope and dead specimens if you are determined to name an ant. The key includes some 15 species new to Britain and Ireland since the original version of the book and this requires looking closely at some quite subtle features, particularly concerning hairs. Simple and clear line drawings help identify the vital body parts before pitching into the full scientific key. This includes an abundance of line drawings alongside the text (c.f. those dreaded old RES Handbooks where they were collected at the end of the book!). Anyone who has previously tried to identify ants has probably looked at a red Myrmica species and puzzled over those antennae, with variously shaped ridges that are difficult to illustrate. The line drawings presented here should help but, as with many such things, having other books to look at may well still be useful. Those daunted by such scientific keys will find a simple ‘quick check field key’ more to their liking and this should allow assignment to at least a small group of options via a flow diagram. My main concern with using such a large, multi-page key in a thick, glue-bound book is trying to keep the thing flat and open while manipulating a specimen under the microscope. Broken book spines may be the result, but such is life!

Two seasoned hymenopterists I know have finally steeled themselves to take a closer look at ants as a result of this book being published and I am sure that many more people will do the same. The information contained therein should not disappoint.