You might think that we already have enough tree identification books but this one is different from the rest. Whereas most concentrate on the trees commonly met in urban landscapes, gardens and possibly arboreta, this one deals with native trees and those naturalised in at least 5% of the 10 × 10km squares of our islands. Moreover, it goes into detail on some of the more difficult native groups that most tree books gloss over and so will be particularly useful for naturalists and conservationists. But it will help beyond this. For example, it includes our two native oaks, plus the best description that I have come across of the Hybrid Oak Quercus × rosacea, and the two commonly naturalised oaks, Holm Oak Q. ilex and Turkey Oak Q. cerris. Also included, however, are five other rarer naturalised and casual oaks which will cover most oaks met in our woodlands.

This book will also have some use in more urban areas since it includes a section on trees widely encountered in parks and gardens (22 species) and another on widespread introductions (23 species). Some care will still be needed. For example, Sawara Cypress Chamaecyparis pisifera is included, but not the cultivar ‘Plumosa’ which is one of the commonest trees in churchyards after our native Yew Taxus baccata. Users of this book should be aware that the trees included do not match those in Stace (2019). For example, Stokes includes Pin Oak Q. palustris and Cork Oak Q. suber while Stace has the Algerian Oak Q. canariensis. Stace also contains some rarer introductions, such as the Pride-of-India/Golden Rain Tree Koelreuteria paniculata, not included in this guide. This does not dimmish the usefulness of Stokes’ book, but it is something to be aware of.

View this book on the NHBS website

If you are new to tree identification or wanting to delve deeper into some of the more difficult groups, then you will find this book most helpful. There are very good introductory visual keys that cover leaves, flowers, fruits and winter twigs to quickly help you narrow the field, and also separate keys for conifer needles and cones. More prominent and difficult families and genera have an introduction with key differences to look for, all well illustrated. Similarly, the difficult genera such as willows, whitebeams and elms are carefully laid out with ample helpful instruction. For example, with the whitebeams Sorbus species there are helpful tables grouping the 39 different taxa and key characteristics. Even more useful are pictures with details of how to count vein numbers, what lobed and unlobed leaves look like in practice, and how to measure depth of lobes. This is just the sort of detail that otherwise leaves a novice floundering. Other books on Sorbus, such as Rich et al. (2010) might give more information and have more detailed keys but I think most naturalists will find Stokes’ book more approachable and easier to use, with other tomes useful for confirming identification and giving more background. There are, of course, limitations and it is beyond the scope of any general identification book to really get to grips with the intricacies of elms and willows, but this book, more than any other, will give you a clearer idea of what you are up against and get you further down the path of definitive identification. It really is a joy to use.

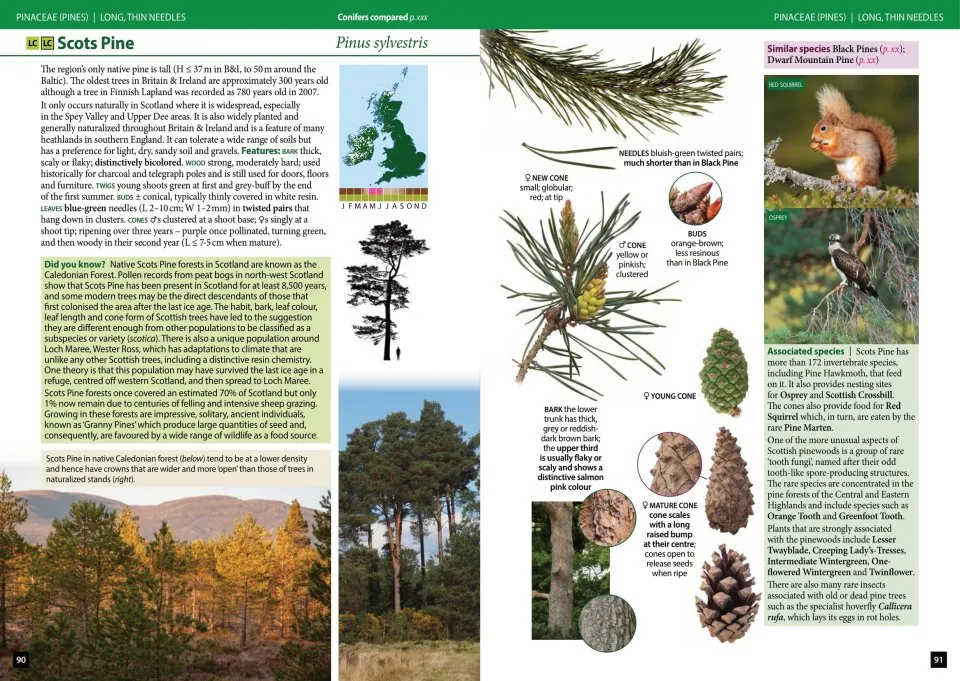

Each tree is well illustrated with excellent photographs of key characteristics, and there is a distribution map and often a drawing of tree shape. This is backed up by boxes with similar species and how to differentiate them. Closely related species often have side by side illustrations of differences. If you have never been quite sure how to tell Austrian pine Pinus nigra ssp. nigra, a common ornamental tree, from Corsican Pine P. nigra ssp. laricio, used in forestry, then look no further.

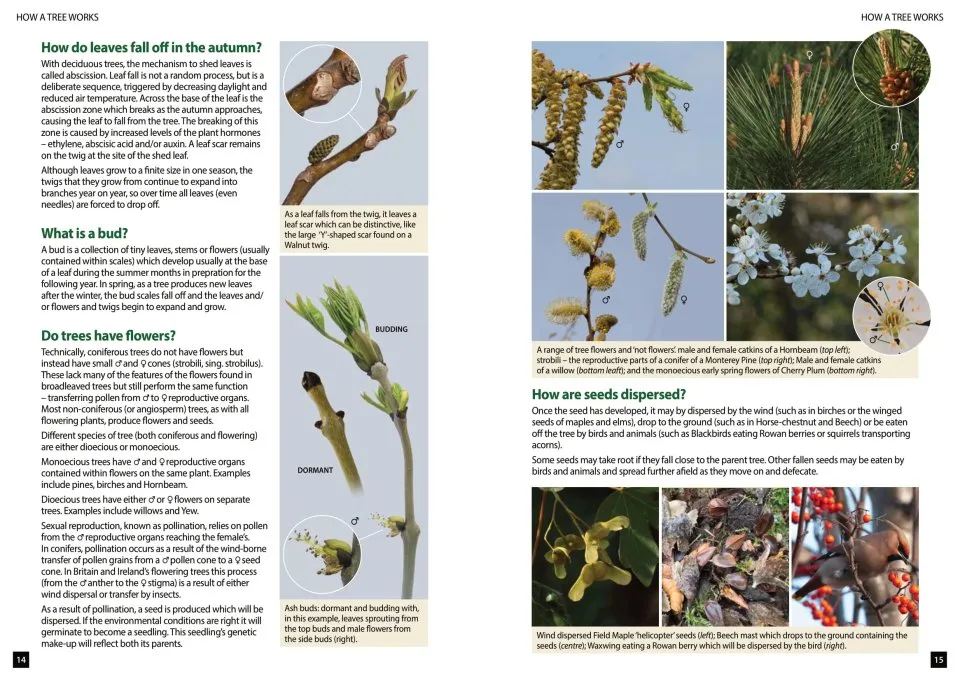

It is important to emphasise too that this is not just an identification book. There are concise but detailed sections at the beginning on how trees grow and why they look the way they do, plant communities with trees, and the history of our trees since the last glaciation. Each tree account comes with a symbol for its conservation status globally and within our islands, and each tree is colour coded to show whether it is native, an archaeophyte or a neophyte. For many of the trees there are ‘Did you know?’ boxes containing interesting snippets of information and often longer boxes on ‘associated species’ covering the most prominent organisms linked to the tree, from fungi to birds. If you are interested in foraging, symbols on which bits can be eaten, and which should be avoided, are given.

Even if you are only vaguely interested in trees, this book makes good bedside reading, as well as being the most useful identification guide to our native trees.