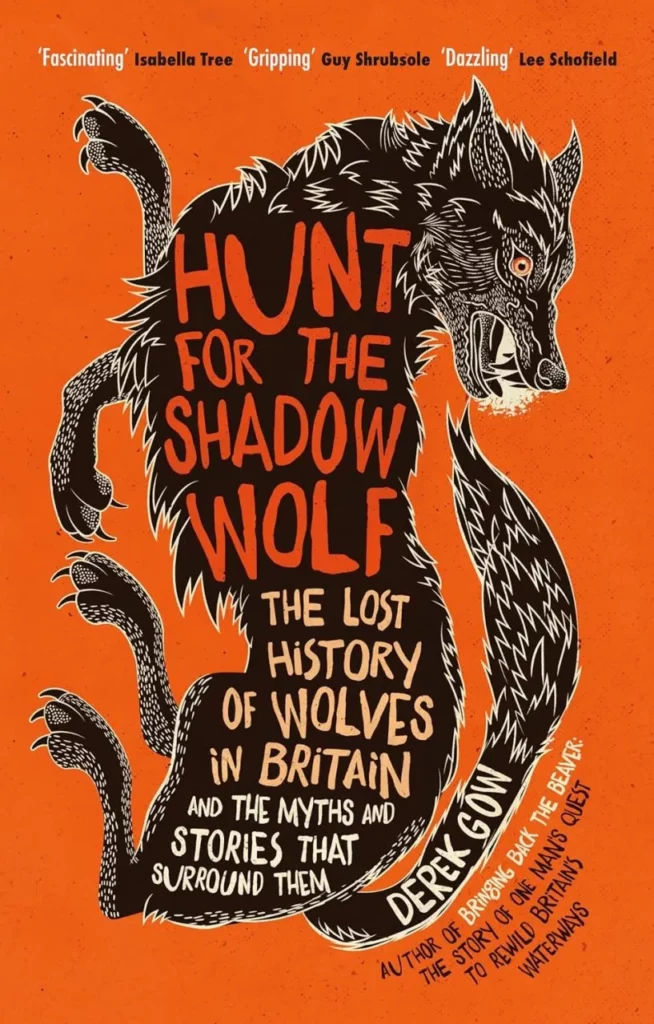

Hunt for the Shadow Wolf

Derek Gow

‘I am no wolf biologist and will not pretend to understand the species well,’ Derek Gow tells us on page 85 of his book, but then, the clue was in the title – Hunt for the Shadow Wolf: the Lost History of Wolves in Britain and the Stories That Surround Them. This is not a dry scientific monograph, or any sort of scholarly review of wolf behaviour. This is Gow’s eclectic and eccentric collection of wolf stories, and in storytelling, Gow excels.

Margaret Attwood once wrote, ‘All stories are about wolves. All worth repeating, that is. Anything else is sentimental drivel’, and one quickly gets the sense that Gow might agree. As a voracious consumer of wolf lore, ranging from the surprising relationships between churchmen and wolves to the gruesome punishments handed out to wolves by vengeful humans, Gow shares with his readers a marvellous menagerie of tales, some tall, some distressing, but all fascinating and all joyously told.

Derek Gow can be a controversial character, and wolves are a controversial subject, so it felt appropriate that this book begins with controversy, and the uncertain tale of the destruction of ‘one of the last’ wolves in Scotland, reportedly slain by one Dougal MacQueen in 1743. The veracity of the tale is corroborated in Gow’s opinion by a contemporaneous written record, but much remains uncertain, as Gow acknowledges.

We’re told that Jim Crumley (another great chronicler of Scotland’s lost wolves) felt that this particular story occurred ‘too late in time’ but that naturalist David Stephen felt the story ‘ought to be true, and may well be.’ In the end, we can’t reliably tell fact from fiction right from the start of Gow’s book, and perhaps that is half the point. Wolves have always been shrouded in exaggeration, hyperbole and myth-making, and Gow leans into this tradition with relish.

Gow outlines a curious paucity of physical proof of the wolf’s presence in Britain after the last ice age, excepting some bones dating from the Middle Ages excavated from Cromarty Castle in Nairn, but describes the abundance of other records that wolves left behind, from records of bounty payments for their capture or death, to the customs records for the sale of their hides. There is a Bronze Age necklace formed of wolf and dog teeth, cross-cut and polished into an ‘admirable ensemble’, and the Ardross Wolf carved into sandstone by a sixth century Pict who clearly ‘understood his subject’s shape.’

We learn that ‘Let him bear the wolf’s head’ was a traditional sentence for criminals who could and should be killed on sight, while many creatures that are not wolves nonetheless bear their name, from the ‘river wolf’ (as otters were once described) to the ‘grain wolf’, a russet field hamster native to the Netherlands. ‘In short, everything that took from us in large or small consequence could be readily described as a wolf and as a result be hated.’

Gow maintains his restless hunt for the wolf in every corner, as ‘one wolf can lead to another.’ He searches for the wolf in place names like Wolf Crag, Wolf River and Wolfhills, but also in older names whose lupine etymology is less obvious, with Wooldale becoming Wolf Dale and Wool Pit becoming Wolf Pit. ‘Wolborough, Wooladom and Woolwell are all likewise masked by the produce of the flock-masters,’ notes Gow, with sheep seeming to have displaced wolves not only from landscape and living memory, but from the long lexicon of wolf-inspired place names.

Before their extirpation from Scotland, Gow tells us that an absence of wolves was once an ‘issue of nationalistic English pride,’ but today their absence is less universally celebrated, and Gow concludes his book with the observation that ‘their appeal is rising.’ Having set out to discover the wolf we once knew, it occurs to the reader that the irony is that we probably know more today of the real wolf than we ever knew in the distant past. Gow begins his account, reflecting that a better account of what happened to Britain’s wolves might ‘constitute a beginning of sorts for any movement that sought their return.’ But amidst all the stories he reflects that, ‘Wolves are just wolves. Nothing more or less.’ That may be, but they have always held a special fascination for us. And as Gow rejoices, ‘We live still in a world of wolves and talk about them all the time.’

View this book on the NHBS website

Reviewed by Hugh Webster