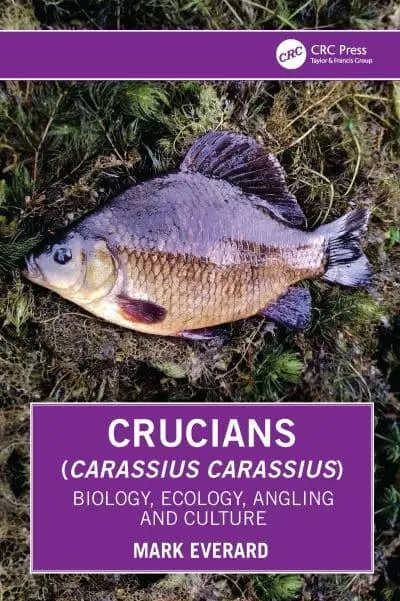

Crucians (Carassius carassius): Biology, Ecology, Angling and Culture

Mark Everard

When I first picked up this book, I was concerned that it could be mired with bloated, so called ‘filler’ text, stretched out to fill the total 114 pages; after all, it really is no easy feat to have this much to say about a single species. Of course, the author, Mark Everard, makes it look easy, having dedicated a number of books to individual species before, including Silver Bream Blicca bjoerkna, Gudgeon Gobio gobio, Dace Leuciscus leuciscus, and more! Every time I feel like there’s not enough information known about a species to make a full (and consistently interesting) book, Mark demonstrates how wrong I am. This publication is the most comprehensive look at Crucians to date, offering a look at their wider cultural importance too.

The book begins with a short introduction, transporting you to picturesque 1960s British countryside, using nothing but words and your imagination. It might seem romanticised now, but the author is painting a perfect picture of what the landscape was like back then. Bomb craters were left to become ponds and sources of water for livestock, ultimately creating a boom in biodiversity and a wider appreciation of fishing for these little ‘golden coins’ which inhabited this network of water bodies. Over the next few decades, however, something changed to virtually eradicate these valuable pockets of wildlife, seeing a catastrophic loss of freshwater fauna, and it all stemmed from a lack of care or disregard for what is going on beneath the water’s surface. The author rallies against these threats, unequivocally celebrating the Crucian across three extensive and well-referenced sections and leaving no room for legislators or industrialists to further ignore or take for granted this species.

What is a Crucian?

One of the earliest passages in this Crucian bible comes from the first section, ‘What Is a Crucian?’; fittingly setting the record straight about their name. While from the wider carp family (Cyprinidae), Crucians belong to the same genus as goldfish (Carassius), not carp (Cyprinus) – we don’t call goldfish ‘Goldfish Carp’, so throughout the rest of the book the author refers to the subject species as Crucians, instead of Crucian Carp. Perhaps a small detail in something as arbitrary as naming, but that continued attention to detail proves to be the book’s greatest asset. The section goes on to discuss morphology, as well as external and internal meristics, accompanied by photographs of prime examples of the species, along with a detailed drawing by the author. All of these are highly useful for readers in an academic environment, but also anyone with a general interest in the species who was not aware that its body shape and colouration can be quite variable, diverging from what they might traditionally see in literature, or in fisheries. This leads into a summary of the types of biomes that Crucians inhabit, and the behaviours which stem from it. This enters into one of the most fascinating parts of the book, detailing how Crucians are able to survive where most (perhaps all) of our other freshwater fish species would perish – the author branding them as having their own set of superpowers. Here the text could have benefitted from photographs of these habitats, especially given the strong theme of celebrating what’s beneath the surface. We don’t actually get to see any Crucians under the water, either, except for those in viewing tanks, although on p. 84 we are graced with a photograph of one of their trademark ‘busy’ habitats, albeit from above the surface – this is only a small criticism. The author poses differing arguments on the definition of native British fishes (given humans’ long influence within these isles), with an excellent background of the geological history, so that you’re informed enough to have an opinion on whether or not Crucians should be considered native, or if it even matters. There are some areas of the book that I had I expected would feel rather redundant, but have been handled quite well. For example, I turned to the pages covering diet, knowing that Crucians are somewhat opportunistic feeders, and didn’t expect them to differ too much from other species of the genus Carassius, but the author has found a way to keep the intrigue by comparing modern records to historic observations (there’s only so many times you can read a list of invertebrates and retain your interest). The penultimate part of this section covers records on spawning and how environmental factors play a role in determining their body shape as the juveniles grow, with notes on parasites and disease you may encounter in these fish; essential reading for a budding fisheries manager. Before transitioning into the middle section, the author’s love of the cyprinids shines through with an extensive overview of their taxonomy, mysteries of their origin, similar species annotated with photographs, and an immensely useful table created for the purpose of discerning species (and hybrids) from one another. I was particularly happy to see our more enigmatic Carassius species make an appearance here, including Gibel C. gibelio, and an uncertain taxon, colloquially called Nigorobuna. Mark uses the name C. grandoculis, although as of 2025, the current status of C. grandoculis on Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes is a synonym of C. auratus and is not given as a species. In any case, this section is exceptionally well referenced, comparable to a scientific report – thanks to Mark’s academic background.

Human Importance

The remaining two sections: ‘Crucian Fishing’ and ‘Crucians and People’, are similar in tone, being that they deal with human interactions with the Crucian; scholars of ethnoichthyology and anglers alike will find these chapters highly informative. The referencing is somewhat lighter here, in comparison to the ‘What is a Crucian?’ chapter, given that much of this comes from the author’s first-hand experiences. In fact, that first chapter feels somewhat like a preface to the text covering angling, as the author pulls together what we’ve learned about their biology and environment to help you better focus your Crucian fishing. To reiterate just how opportunistic Crucians can be, the author was able to dedicate 13 pages to covering bait, lures and their presentation alone! Angling historians will also enjoy the coverage of rod and line records, and how the British angling scene has shifted to better accommodate modern Common Carp anglers. Finally we come to the jewel in the crown, as Mark hypothesises on why we’re so enamoured with Crucians, providing a lesson on their importance in arts, cuisine, and aquaculture. I won’t unravel this chapter any further, but if the first half of the book was focused on the form and rigidity of defining what a Crucian is, then this second half beautifully tells us why we should care; fittingly, closing with a panoptic look at their conservation.

Crucians (Carassius carassius): Biology, Ecology, Angling and Culture is honest from the start, doing exactly what is says on the tin, yet somehow it undersells itself. Covering a single species with as much detail as this, is nothing other than a love letter, and you can’t truly appreciate this until you leaf through.

Reviewed by Joshua Pickett