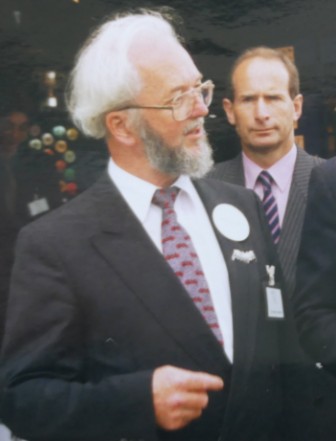

Fifty years of bat protection in Britain: in conversation with Bob Stebbings

This year marks half a century since bats were first given legal protection in Britain. The forthcoming June issue of British Wildlife features a personal reflection from Bob Stebbings, one of the founding figures in bat conservation, on the remarkable story behind the battle to gain protection for these animals. Ahead of publication, we spoke to Bob about his involvement in the campaign and how the legislation has changed our treatment of bats.

For a generation which is broadly sympathetic to the needs of bats, the persecution inflicted on these animals in the not-so-distant past seems almost incredible. “People used to deliberately kill them’, Bob says, “including local councils who would instruct their ‘rat catchers’ to kill bats if a complaint was received from a property owner”. Sensitivity around roosts was similarly non-existent: entrance holes were routinely blocked, causing bats to die within or to be excluded from important spaces required for their survival.

Bats were also unintended casualties of changes in domestic pest-control during the mid-20th century. “After the Second World War, organochlorine pesticides such as DDT, Lindane and Dieldrin were becoming extensively used by the timber preservation industry for treating all kinds of buildings, resulting in the deaths of bats”, Bob recalls. These chemicals could have a catastrophic impact on individual colonies, and witnessing one such case was instrumental in triggering Bob to act: “It was in 1961 when I came across a building treated in the mid-1950s, leading to the poisoning of thousands of Greater Horseshoe Bats. The company director carrying out the treatment was upset about what had happened when I contacted him.

“Twenty-seven years later the pesticide was still detectable in the huge roof. A few Greater Horseshoe Bats continued to give birth there even 30 years after, but their newborn never grew and died before weaning. This, we assumed, was caused by low levels of the pesticide in the air.”

Coupled with observations of falling bat numbers, Bob was convinced that change was needed to prevent further losses, but he faced a formidable challenge. Large portions of the general public were actively hostile towards bats, for the nuisance they could cause in homes and for their cultural associations with evil, which meant that politicians had little incentive to fight their corner. “They were feared, not understood in any way, and the subject of many horror films,” Bob says, “and whenever bats were mentioned in the media, they were creatures to be hated and avoided.”

Undeterred, and to the occasional exasperation of his employers, Bob set about trying to rally support for bats alongside his main work on saltmarsh ecology for the Nature Conservancy. Starting in the early 1960s, his approach was twofold: “firstly, I decided that the wider public needed to know about the life history of bats and their sensitivities to all kinds of problems, in order to encourage tolerance and concern for bat survival. Secondly, we needed to gather documentary evidence on how bats were being impacted by events that could be controlled by law. Then it became important to persuade champions in parliament – both houses – to carry forward the development of bills which, after due discussion and processes, would become enacted legislation.”

Greater Horseshoe Bat, Bob Stebbings

The persistence of Bob and collaborators ultimately paid off, the first victory coming in 1975 when the Conservation of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants Act gave full protection to two bat species, the Greater Horseshoe and the Greater Mouse-eared Bats. This paved the way for the eventual protection of all bat species, which entered law in 1981 in the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. This Act underpins the legislation affecting bats and their roosts to the present day, giving them a level of protection that remains unprecedented among wild mammals. “Perhaps the largest effort was changing public opinion concerning bats,” Bob reflects; “years of getting time on radio and television to say that ‘bats are lovely’, with some story about the research we were doing, gradually helped to promote bats as creatures warranting our help. In my opinion, bringing about that change took 15 years, plus the first [1975] legal protection which helped draw attention to their plight.”

Bob believes that the legislation had an instant positive impact: “the Nature Conservancy Council not only had to arrange for a licensing section to administer the Act in relation to the capture and handling of bats for marking (ringing mostly), but many of its officers were keen to assist in survey and in protecting important roosts and other habitat.”

And what of the wider negativity towards bats? “The public and to some extent the media all began to be more sympathetic towards bat issues”, Bob says. “Generally bats are now regarded simply as an important part of Britain’s wildlife. Throughout the year thousands of people all over the country go out to record colonies or watch bats at night, and it seems that all the media play their part in promoting bat welfare.”

Greater Mouse-eared Bat, Bob Stebbings

Given the monumental effort involved in achieving protection for bats, it is concerning that this milestone anniversary comes at a time when their future protection has been cast into doubt. The UK Government’s proposed Planning & Infrastructure Bill (P&I Bill), while not yet finalised, has been condemned in its current form – including by Bat Conservation Trust – for its potential to erode environmental safeguards, and permit destruction of protected species with no guarantee of any corresponding gains.

Bob highlights the way in which ill-conceived mitigation projects have been used to paint existing bat legislation as a blocker to development. “There has been much erroneous commentary in relation to the greatly publicised HS2 ‘bat tunnel’, costing £100 million. That was never recommended by bat advisors, but was decided by HS2 planners. Yes, there are rare bats living in that area and bats are killed by vehicles of all kinds, including trains, but there are various ways of carrying out mitigation which could be used at a fraction of the cost.

“Clear excesses in required work have not helped wildlife protection and have made companies and now government think that wildlife gets in the way of development.”

Bat protection has been one of the great triumphs of British conservation, and many bat populations are showing long-term recovery. Of the two species to first benefit from protection, the Greater Horseshoe, while still rare, is rapidly increasing and recolonising former parts of its range, while recent sightings have offered cautious hope that the Greater Mouse-eared Bat could again breed here in future, after being declared nationally extinct in 1992. From this relatively secure position, it is easy to forget how much worse things were for bats before protection existed: we must now ensure that the P&I Bill does not undo the hard work involved in reaching this point.

A full account from Bob Stebbings on the history of bat protection in Britain will appear in the June issue of British Wildlife.