On Natural Capital: The Value of the World Around Us

Partha Dasgupta

Published just over four years on from the eponymous review on The Economics of Biodiversity, Sir Partha Dasgupta’s On Natural Capital could not have come at a more exasperating, and timely, moment. Four years of continually missed national and international climate and nature targets; four years of political regression on previous consensuses; and four years of increasing awareness and understanding of just how dire things are — and will become. A translation of the 600-odd-page Dasgupta Review for the general reader, On Natural Capital attempts to explicate the systemic economic underpinnings of that very exasperation — and to provide a roadmap thereout.

On Natural Capital amounts to a discursive textbook, putting forth more a summative theoretical than a grand rhetorical thesis on its named topic. Laid out across ten chapters, it treats the subject of that topic with subservient authority. Nature is spelled with a big — not little — n. And her exploitation, whether present or past, can primarily be pinned on our broken (economic) relationship with that which she provides. (Though not my area of expertise, it would still be worth exploring this feminisation. An ecofeminist reading of this and related works would be of interest.)

Dasgupta pushes back against what he calls ‘an elaborate exercise in collective solipsism’; traditional economic thought and the systems derived therefrom are framed as temporally and ecologically bankrupt. He foregrounds foundational ecological concepts — the basics of biodiversity, whether food webs, speciation, carrying capacities, or species-area relationships — and humanity’s temporal finitude relative to the natural world it inhabits. The natural world’s relative complexity, too, is emphasised. Economic systems are thereby subordinated in time and in complexity — being comparatively simple to that which they seek to manage: ‘if human history is a mere blink in the story of the biosphere, economic history in turn is a tiny fraction of that’ (p. 59).

Economic concepts are broken down as well — different types of capital, goods, and services in particular. Capital becomes human, natural, and produced; goods and services become provisioning and regulating. This stands to be the central thrust of the book: that the origin of our ecological demise is the conflict between demand for provisioning goods — the physical material, like wood, water, and the fruit of soils, that we use — and our basic need for the maintenance and regulating services — like clean air, carbon storage, and pollination — that the sources of those provisioning goods provide.

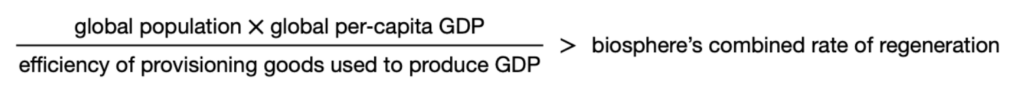

Dasgupta proceeds to outline the sheer decline the natural world has experienced over the last two centuries, like a quarter of our tropical forests facing our collective chainsaw since the first Convention on Biological Diversity in Rio, back in 1992. This is put down to a poorly weighted Impact Inequality — the idea that total ecological overreach can be measured by the following equation:

He is honest about the limitations of this framing and the nuances it can shroud, instead emphasising the reality that the biosphere’s rate of regeneration needs to be buttressed while the provisioning goods we consume (and maintenance services we rely upon) need to be priced more honestly and efficiently. And this follows through in the set of interventions Dasgupta proposes.

Pigouvian taxation, for one, is floated. This is the idea that negative externalities — the unpriced impacts the production of a good entails, like the pollution of a river by an upstream gold mine — are incorporated into the price of goods, thereby de-incentivising their consumption and recompensing damage through subsidy should consumption be necessary. Dasgupta also discusses the importance of economic and non-economic norms: the social structures that guide individual, corporate, and governmental behaviour and foster shared understandings of civic life. And while he doesn’t dismiss the use of GDP as an economic indicator outright — it being ‘useful for short-run macroeconomic management’ — he posits an alternative, parallel, system of capital accounts that includes natural capital and emphasises economic stocks rather than flows. This, Dasgupta claims, would address ‘the fact that we have accumulated produced capital and human capital in the Anthropocene but have degraded natural capital to an extent that we have been endangering our collective futures’ (p. 168-169). In addition to this, governance reforms, corporate disclosure, and behavioural changes are floated. An international fiscal and regulatory body for oceans is proposed for the first; mandatory disclosure of supply chain conditions for the second; and the use of nudge theory to change individual consumptive behaviour for the third.

On Natural Capital is a historically astute and circumspect work. Some aspects, though, like these proposed (policy) interventions, could be bolstered. His discussion of international governance frameworks, for one, excludes critiques of today’s nation state-centric system of international law (or lack thereof) — and how that system limits the planetary interventions needed to arrest ecological decline. The discussion of corporate disclosure, too, has an air of inappropriate scale, while nudge theory has a similar feeling of spatiotemporal impotence.

This (relative) impotence becomes especially stark in the book’s last chapter, where Dasgupta expounds on what he believes to be the intrinsic value of the natural world and our inherent, embedded, interconnectedness with her. He argues that the idea of the self, a core unit in economic thought, should be expanded — escaping the dualist separation between the self and the inextricable environment around it. ‘Intellectualising our place in Nature misses something of supreme importance; the emotional attachment to her that we feel we are in danger of tearing apart’ (p. 207). Yet creating an economic relationship with her at the scale proposed does feel like continuing to tear at that very attachment, despite Dasgupta’s claims that ‘the fault is not in economics’, instead lying ‘in the way we have chosen to practise it’ (p. 205).

Further improvements could have come in the integration of political economy and consumption inequality. Consumer, corporate, and state preferences — while not painted as unshaped by non-economic incentives — should have been explicitly discussed in the context of their being shaped by malign interests, whether by the fossil fuel industry or others. The warping of per capita consumption by disproportionately high consumers — think the billionaires and technology brothers of this world — could have been explicated too. Related emphasis on human population growth is put into perspective when the likes of Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos emit six orders of magnitude more carbon than the average Brit (although, granted, their nature-centric footprints are less clear). Further discussion on production efficiency, and the ability to produce more provisioning goods with lower impacts on maintenance and regulating services, would have been welcome too — particularly in relation to Jevons Paradox, the idea wherein higher production efficiency incentivises higher total production, and therefore results in higher total impacts.

One other substantial issue Dasgupta could have elaborated on was his discussion of the Tragedy of the Commons. This concept, coined originally by H. Scott Gordon in 1954 but popularised by Garrett Hardin in 1968, describes the way ungoverned common resources are exploited by human actors and communities out of fear of other actors’ and communities’ exploitation and relative gain. Emphasis on ungoverned commons was lacking, and while admitting that current private property regimes similarly do not value natural capital and are thereby little better, and while also admitting that communitarian norms-based small-scale commons governance can actually be effective, the narrative throughout On Natural Capital does not maintain this same level of nuance. And lastly, at risk of sounding overly critical, Dasgupta could have discussed how economic systems can better consider non-linearity — given the systemic cascades and tipping points we are likely to experience in the coming decades. Their mention in the book’s first chapter proved too brief.

All this considered, On Natural Capital does amply fulfil the mission set out for itself: to act as a textbook-like introduction for those interested in exploring the topic. Dasgupta writes accessibly, and when discussing key mathematical concepts provides plenty of examples. It is worth the read, particularly for those who do not have The Economics of Biodiversity sitting on their shelves!

Reviewed by Ted Theisinger

Ted is an independent writer and researcher with a background in environmental history. His specialism lies in the intersections between rewilding, land governance, and landownership in Scotland and the UK, with his research focussing on future-centric systems change. Ted is a keen hillwalker, train-travelling enthusiast, and allotmenteer.